Sermon for the Feast of St. Isaac the Syrian (2014)

Several years ago during a long car ride, a monk from another shared a little of the story of his coming to the monastic life after an at best nominal Orthodox upbringing. He and his brother had been baptized as infants through the influence of a Orthodox Christian grandmother, but had rarely attended Church, and were not given any religious instruction as they grew older. As an adult, impelled by a spiritual longing or hunger, the likes of which have brought many of us to the doors of the Holy Church, he received the catechism so long delayed, and in time left the world to devote his life wholly to Christ.

After he had spent a year or so as a novice, he accompanied some of the brethren to a parish festival where the monastery had been invited to set up a booth to sell books and Church items. The parish happened to be the very one where he had been baptized, and during the course of the visit several elderly parishioners came to greet him and to tell him, “We are so happy to see you. Your whole life, we have been praying that you and your brother would come back to the Church.” He was very moved by this, struck with the realization that his monastic vocation was in a real sense the fruit of prayers of which he had been completely unaware, offered to God by benefactors he did not know. And now he, striving to live the ascetic life, will pray for them daily for the rest of his life. I do not believe that these elderly men and women were motivated in their prayers by a desire for reward, or anything other than a pure love for the two boys they had seen baptized as children, but what a reward they gained: the prayers, the personal intercessions, of someone who has forsaken—and strives each to forsake—all else for the love of God.

It often happens that at some point in time we experience a dramatic turn for the better, for instance recovery from a long physical illness or a renewed resolve to repent of our sins from the heart, and later find out that it was just at that time that a spiritual father or one of our brothers or friends had been praying for us with special fervency. Truly, we are all deeply connected to one another, and this is so not only of those whom we call friends but even those whom we find difficult to be around, and indeed those who hate us. In the Gospel for this Sunday, Christ admonishes each of us with the words, “As ye would that men should do to you, do ye also to them likewise. For if ye love them which love you, what thank have ye? for sinners also love those that love them.” And if we have ourselves been greatly assisted be the unknown prayers of anonymous benefactors, and desire the same in the future, despite our many faults, how better can we fulfill this commandment than to offer God daily, fervent prayers in behalf of others, both those who hate us and those who love us? This is at once the duty of all Christians and the special calling of the monk, who more than other Christians lives in an environment free from worldly concerns and who strives to make prayer his primary occupation. As Abbot Damascene of the Platina monastery has written:

[A] monk on leaving the world does not at all cease having love and concern for the world, nor does he cease to labor for it. His love and his labor for the world are expressed in his prayers for it. He actually helps to sustain the world through his prayers.

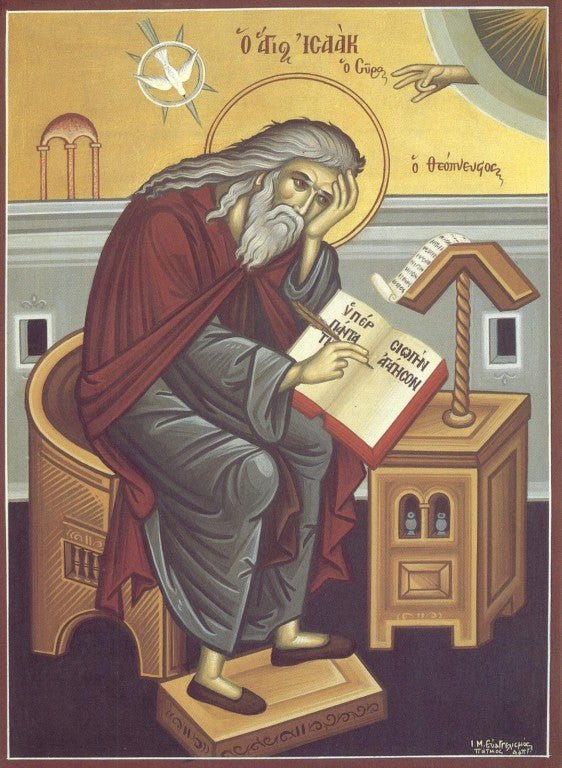

Today, as we celebrate the memory of St. Isaac of Syria, bishop of Nineveh and one of the greatest solitaries in all of Church history, a monk par excellence, we cannot help be reminded of this principle. Obedient to the command of God and in accordance with the bountiful grace bestowed upon him, St. Isaac forsook the world not only outwardly but cut off all affection for worldly things. He was an ascetic the likes of which one could hardly find today. Even active Church service was for St. Isaac an unacceptable distraction from the one thing needful, and although as a bishop he had received the fulness of the grace of the priesthood, he remained in his office in Nineveh for only five months before returning to the desert and his ascetic labors, preferring the life of the simple monk to the outward exercise of the episcopacy. In this state of desert solitude and asceticism, his prayers and his love embraced not only humankind as a whole, but all of God’s creation, not excluding the demons themselves. In short, he loved all, both those who loved him and those absolutely incapable of loving in return, and as a true monk this love was expressed chiefly in his pure prayers for them. In one of his recorded prayers, he addresses God with these words:

May there be remembered, Lord, on Your holy altar at the fearful moment when Your Body and Your Blood are sacrificed for the salvation of the world, all the fathers and brethren who are on mountains, in caves, in ravines, cliffs, rugged and desolate places, who are hidden from the world and it is only known to You where they are—those who have died and those still living and ministering before You in body and soul, You the Holy One Who dwell in the holy ones… O King of all worlds and of all the Orthodox Fathers who, for the sake of the truth of the faith, have endured exile and afflictions at the hands of persecutors, who in monasteries, convents, deserts and the habitations of the world, everywhere and in every place, have made it their care to please You with labours for the sake of virtue… I beg and beseech You, Lord, grant to all who have gone astray a true knowledge of You, so that each and every one may come to know Your glory.

Not all of us can live in the perfect silence and solitude that characterized this saint’s life, and it would equally be unreasonable to expect to attain to the same heights of prayer. Nevertheless, we can thank God for and try to make the best use of the opportunities for silence and solitude He provides to each one of us whatever our manner of life may be. A few minutes of the hundreds of minutes God gives us in each day, an akathist or prayer rope said for someone when the opportunity arises, may benefit him more than he or we will ever know. Not all of us can sincerely pray for demons—in fact it may be spiritually detrimental for those of us who have not been sufficiently purified of the passions—but we may all show mercy to those who are unkind and unmerciful to us, and pray for them as we would hope that they pray for us. Not all of us can be entirely free of cares, whether purely worldly ones or those of an ecclesiastical nature, but we can all avoid voluntarily filling our minds with gossip, rumors, and vain conversations that neither concern nor in any way benefit us, but only sap our mental energy and render us disinclined toward prayer. If we cannot in every detail emulate the life St. Isaac the Syrian, we can learn from him a little at a time, applying his example and teaching according to our spiritual state, just as it has been the custom in this monastery to read just one page per day from his Ascetical Homilies, becoming through his holy prayers and as he became before us, merciful, as our heavenly Father is merciful.

Through the prayers of our venerable Father Isaac, Lord Jesus Christ our God have mercy on us. Amen.

Leave a comment