St. Anthony the Great and the Beautiful Life

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER, AND OF THE SON, AND OF THE HOLY SPIRIT. AMEN.

Introduction

St. Augustine (born in the second half of the fourth century) writes in his Confessions, that around the time of his conversion, is when he first encountered the name of St. Antony from a friend who was surprised that he had not heard of him yet. He writes:

I told him that I had given much care to [the Scriptures]. Whereupon he began to tell the story of the Egyptian monk Antony, whose name was held in high honour among [God’s] servants, although… I had never heard it before that time. When he learned this, he was the more intent upon telling the story, anxious to introduce so great a man to men ignorant of him, and very much marveling at our ignorance. But… I stood amazed to hear of [God’s] wonderful works, done in the true faith and in the Catholic Church so recently, practically in our own times, and with such numbers of witnesses. All three of us were filled with wonder, we because the deeds we were now hearing were so great, and he because we had never heard them before.

From this story he went on to the great groups in the monasteries, and their ways all redolent of [God], and the fertile deserts of the wilderness, of all of which we knew nothing. [1]

Only two works are attributed to St. Antony the Great, a work entitled Counsels on the Character of Men and on the Virtuous Life, which consists of “170 Texts,” and a collection of seven letters attributed to him and translated into English by Derwas Chitty. In the Apophthegmata Patrum, there are also thirty-eight sayings attributed to St. Antony.

Many of us are familiar with his life as written by St. Athanasius the Great, a short work consisting of only seventy pages. This work, The Life of Antony, quickly circulated throughout the whole Christian world of the time. It is known in 165 manuscripts in Greek alone, but also found in Latin, Coptic, Syrian, and Georgian translations.[2]

Our knowledge of St. Antony’s life and work is very brief yet to all of us he is St. Antony the Great, and we know him as “the Father of Monasticism” but not because he is the first monk, because there had been many ascetics living in the cities and the deserts, in communities and alone, but he is the first to organize his disciples into unique monastic communities which continued on from that time with the particular ascetic regimen which he taught. His was not the only form of ascetic life, but it was the one which healed the soul most directly.

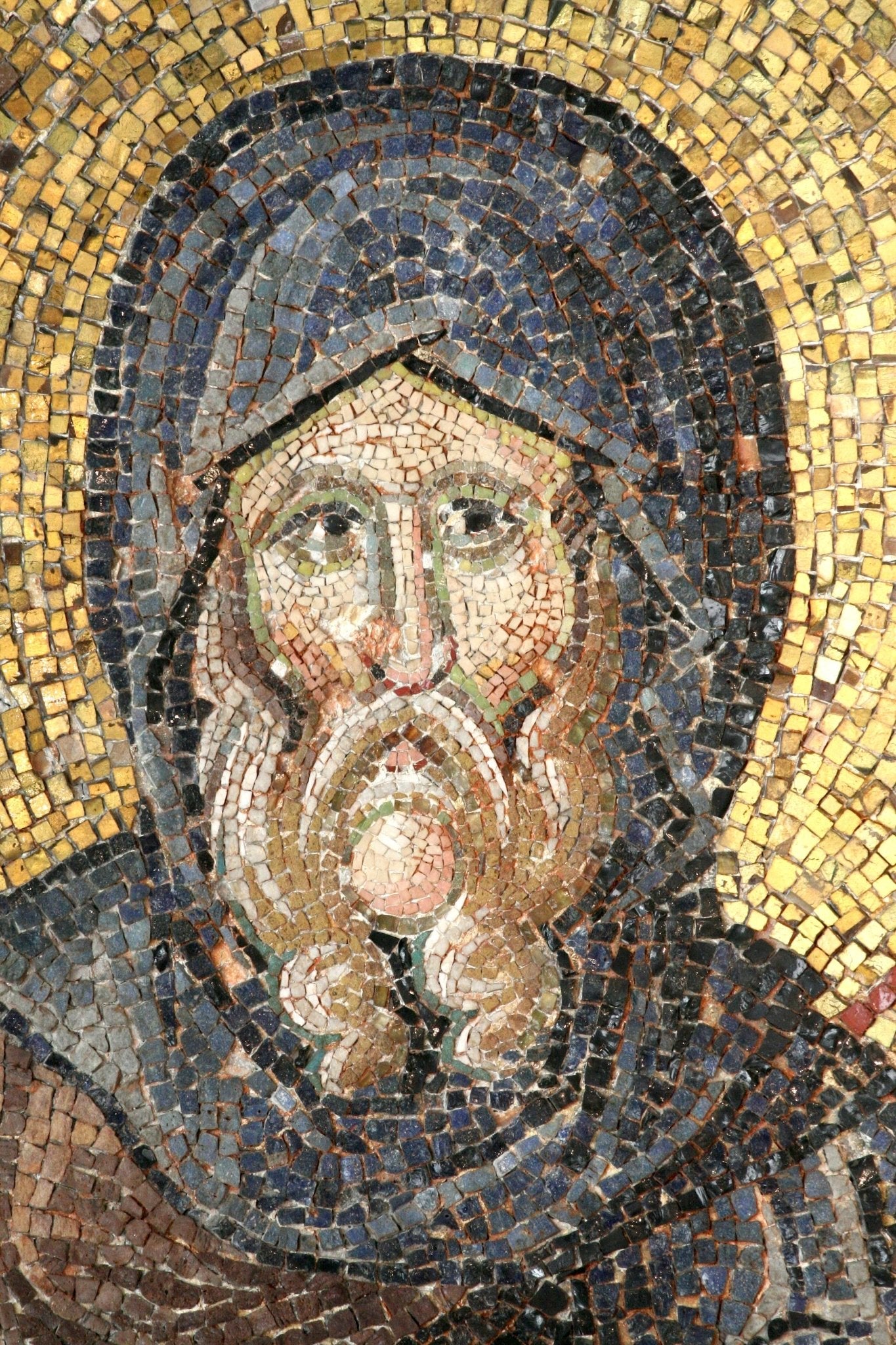

The Life of St. Antony

St. Antony was born in the year 250 and reposed 105 years later, in 355. At about the age of nineteen, after his parents had recently died, Anthony went into a church to pray; while there he heard the Gospel passage: “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven” (Matt. 19:21). Believing it to be God’s command for him, he distributed all of his belongings and went to live with a man who had practiced the solitary life from his youth.[3] Gradually, he moved further into the (Nitrian) desert for greater isolation until at last he came to an abandoned fort in which he secluded himself from the outside world for twenty years. Here he engaged in a spiritual struggle with devils, heat, cold, hunger, and deprivation.[4] When Antony eventually concluded his isolation, he emerged not looking withered or emaciated but as Adam in Paradise, a man restored to his original glory, not as a starved and languishing man. This end of his seclusion would be the beginning of his public ministry which included the healing of the sick, casting out demons, and the consolation of the sorrowful. In a short time, other ascetics gathered around him to learn this monastic life, or, as it has was stated by St. Athanasius, “from then on there were monasteries in the mountains and the desert was made a city by monks, who left their own people and registered themselves for the citizenship of the heavens.”[5]

There are many unique aspects of St. Athanasius’ work, The Life of Antony, but one which is worthy of note today is the description that St. Gregory the Theologian offers about this life. He says that St. Athanasius had, “composed a rule for the monastic life in the form of a narrative.”[6] What the work became was the first life of a saint, and the beginning of that genre - hagiography. As St. Athanasius himself writes in the Introduction to the life, compiling his life at the request of monks who lived outside of Egypt, he writes, “For simply to remember Antony is a great profit and assistance for me also. I know that even in hearing, along with marveling at the man, you will also want to emulate his purpose, for Antony’s way of life provides monks with a sufficient picture for ascetic practice.”[7]

One contemporary scholar, writing about the significance of “imitation” notes that, “unity through the sacraments was a common enough idea among early Christians; Athanasius’ more distinctive theme was that, as individual Christians formed themselves by imitating the saints way of life, they formed a corporate commonwealth… Diverse as the ways of following the saints may have been, their common origin in Christ and their actualization through imitation gave them their unified character as a single way of life.”[8]

The Teaching of St. Antony on the Ascetical Life

It is about this life which is worthy of imitation that St. Antony frequently speaks.

At the beginning of the work entitled Counsels on the Character of Men and on the Virtuous Life, we read that the truly rational man is he who discerns good and evil and learns to do the one and shun the other:

Men are improperly called rational; it is not those who have learned thoroughly the discourse and books of the wise men of old that are rational, but those who have a rational soul and can discern what is good and what is evil, and avoid what is evil and harmful to the soul, but zealously keep, with the aid of practice, what is good and beneficial to the soul, and do this with many thanks to God. These alone should be called truly rational men.[9]

It is this life which he terms as the most “beautiful life,” the κάλλιστος βίος, and says,

Meditation on the most beautiful life (κάλλιστος βίος) and care of the soul render men good and God-loving. For he who seeks God finds Him by overcoming desire in all things, not shrinking from prayer. Such a man does not fear demons.

Those who are deceived by worldly hopes and know the things that must be done for the most beautiful life (κάλλιστος βίος) only so far as words go, are in the same state as those who are furnished with medicines and medical instruments but neither know how to use them, nor take the trouble to learn. Therefore, we must never blame our birth nor anyone else but ourselves as the cause of our sinful actions; for if the soul chooses to be in a state of indolence, it cannot remain invincible.[10]

Moreover, as the above scholar noted, St. Antony was not a philosopher, no he was a practioner of the Christian way of life. It was by living this life that he learned and therefore taught that meditation on the beautiful life, makes one good even if only he begins to desire to become good.

St. Antony and all the saints are a model on which we can meditate, and imitate, and learn, even as they are imitators of Christ, as the Apostle Paul says of himself, “Imitate me as I imitate Christ” (1 Cor. 11.1).

The Ascetic Life as the Angelic Life

There are many people nowadays who enjoy reading, writing and giving podcasts about the Second Temple Period of Judaism and about Apocalypticism, and the religious experience of the Jews with the heavenly realm whether it be with angels or being transported to Heaven or to the Heavenly Temple. A similar example can be seen in the life of St. Antony, though not limited only to him, and which was known by many even from St. John Climacus (6th century) to St. Isaac the Syrian (7th century). In Step 19:7 of The Ladder of Divine Ascent, St. John writes that St. Antony was taught by angels. St. Isaac writes,

But what need is there to speak of the ascetics, those strangers to the world, and of the anchorites, who made the desert a city and a dwelling-place and hostelry of angels? For the angels continually visited these men because their modes of life were so similar; and as being troops of a single Sovereign, at all times they kept company with their comrades-in-arms, that is to say, those who embraced the desert all the days of their life, and they took up their abode in the mountains and in dens and caves of the earth because of their love for God. And since, having abandoned things earthly, they loved the heavenly and were become imitators of the angels, rightly did those very same holy angels not conceal the sight of themselves from them, and they fulfilled their every wish… Moreover, from time to time they appeared to them to teach them how they ought to lead their lives.[11]

Conclusion

Although one should never be looking for miracles, let alone angels, as a confirmation of one’s way of life or as a sign of one’s being pleasing to God, or some other reason for testing God, nonetheless it is not foreign to our hagiography. However, the most important aspect is not the manifestation of divine signs but our imitation of those who were pleasing to God, who lived the virtuous life, the truly beautiful life, and which makes one wise, and good, and manifests ones love for God. Or, as St. Antony writes, it is the κάλλιστος βίος for, at least, three reasons:

- that he who draws near to grace will know himself and in turn will know God (Letter 2 [14], Letter 3 [16]);[12]

- when the soul gives itself to God wholeheartedly, God has mercy on it and grants it a Spirit of Repentance which testifies to the soul about each sin, and delivers that soul from its effects (Letter 1, [7]); and

- all who are taught by the Holy Spirit know what God has given them all the virtues, unless we defile our heart and body by sin (Letter 4, [17]).

Through the prayers of St. Antony the Great, may we learn how to please God in our lives, in our thought and in our actions, and may we meditate on his life, imitating him where it is beneficial, and glean that which is most advantageous for each of us.

THROUGH THE PRAYERS OF OUR HOLY FATHERS, LORD JESUS CHRIST OUR GOD, HAVE MERCY ON US. AMEN.

[1] St. Augustine, Confessions, F.J. Sheed trans. (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2006) Book 8, Ch. 6 (182).

[2] Drobner, Hubertus R. The Fathers of the Church: A Comprehensive Introduction. Siegfried S. Schatzmann, trans. (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2007), 379.

[3] As with St. Pachomius, St. Anthony learns from an experienced monk before setting out on his own.

[4] The Life of Antony, Sec. 6.

[5] Athanasius: The Life of Antony and the Letter to Marcellinus. Robert C. Gregg, trans. (Mahwah, Paulist Press, 1980), 42-43.

[6] Harmless S.J., William. Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 69.

[7] Athanasius: The Life of Antony, 29.

[8] Brakke, David. Athanasius and Asceticism. (Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1995), 163, 165.

[9] “Counsels on the Character of Men and on the Virtuous Life” in The Philokalia, Constantine Cavarnos, trans. (Belmont: Institute for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 2008), 43.

[10] Ibid., 54-55.

[11] The Ascetical Homilies of Saint Isaac the Syrian, Holy Transfiguration Monastery, trans. (Boston: Holy Transfiguration Monastery, 2011), 158-159.

[12] Cf. The Letters of Saint Antony the Great, Derwas J. Chitty, trans. (Oxford: Fairacres Publications, 2014).

Leave a comment