Compassion and the Sicknesses of Soul and Body: A Homily on the 25th Sunday after Pentecost

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER, AND OF THE SON, AND OF THE HOLY SPIRIT. AMEN.

Introduction

From the beginning of Luke chapter 10, the Lord is addressing the topic of sin and suffering. He introduces the topic by bringing to the attention of His listeners those Galileans who were killed on Herod’s birthday, and whose blood Herod mixed with sacrifices. The Lord asks, “Can we conclude that these Galileans were greater sinners because of the way in which they died?”(vs. 1-2). He continues and asks about those eighteen people on whom the tower of Siloam fell, and they all died, “were they worse than other men?” To this, He answers, “No” (vs. 3).

Narration

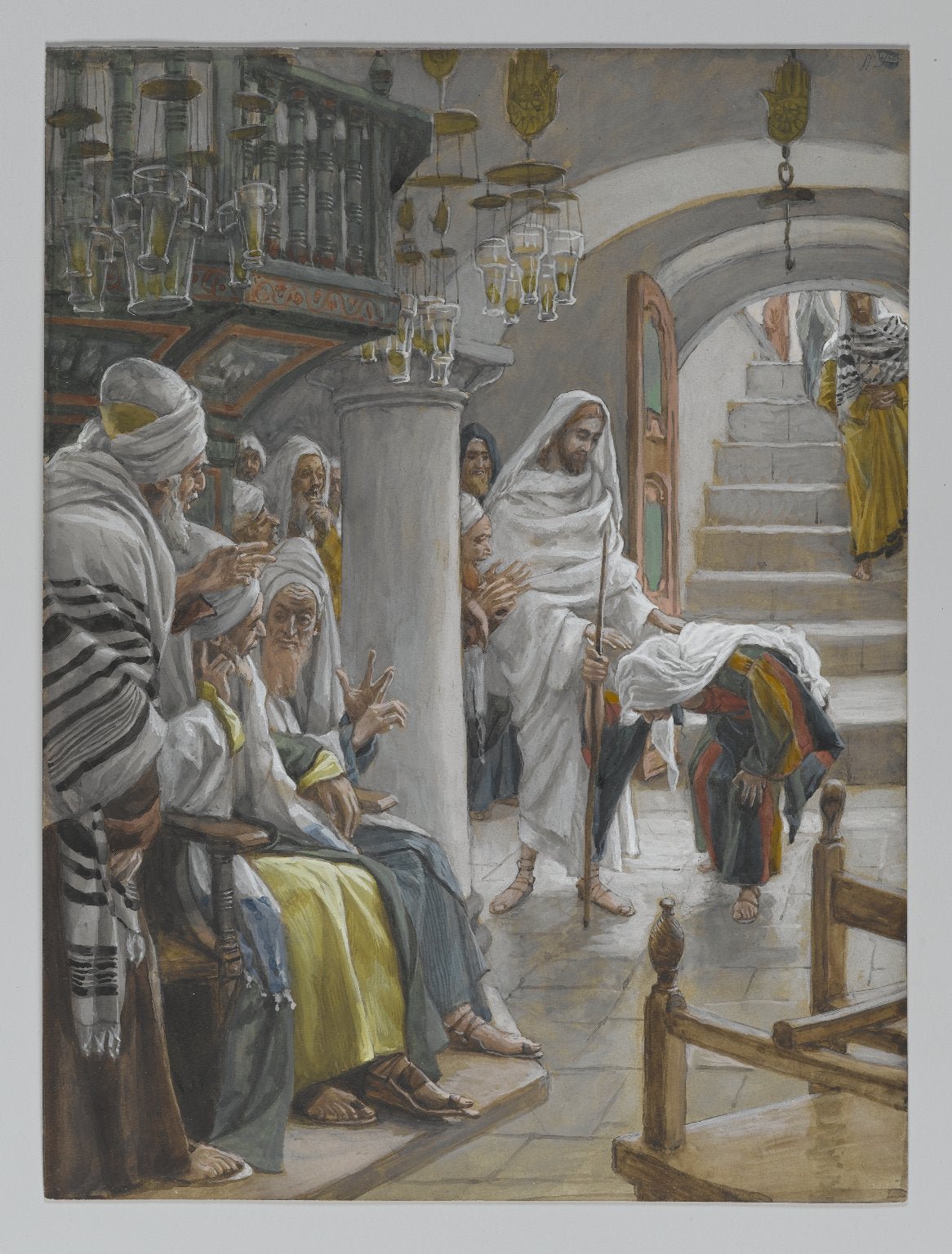

The account, which we have just heard, is found only in the Gospel of Luke. It speaks of Jesus, being in the Temple on the Sabbath and encountering a woman who was bent over forwards for eighteen years. This ailment is described as a “spirit of infirmity”(vs. 11) under which she was unable to straighten herself up. Jesus gives no indication as to the cause of the infirmity, except to say that she has been “bound by Satan” (vs. 16). He called her to Himself and said to her, “Woman, thou art loosed from thine infirmity.” And he laid his hands on her: and immediately she was made straight (vs. 12-13).

The Value of the Body

We should note the value that Christ places on the physical body. As we all know, this is only one instance amongst many where Christ is healing the sick, and yet health and wholeness of the body do not mean that one more easily communes with God. When Christ heals the ten lepers, only one returns to Him in thanks and glorifying God (Luke 17.11-19). Almost the opposite inference is the case because we read of many lives wherein great saints suffered, and then other stories where the bodies of sinners flourished with health.

The Apostle Paul’s entire life was one of suffering which he did not consider as something that distanced him from God. (One may also recall the lives of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia as well as the contemporary Romanian elders who were tortured and did hard time in the communist prisons.) Although we see that the Apostle Paul bore a “thorn in his flesh,” which the Lord did not release him from, many other times did the Lord heal the sick not only to show that He was Lord over the soul and the body but to demonstrate to us the high value of the body. One is not raised from the dead in soul only but in soul and body. “For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality,” writes the Apostle Paul (1 Cor. 15.53). “[The body] is sown in corruption; it is raised in incorruption: It is sown in dishonor; it is raised in glory: it is sown in weakness; it is raised in power” (Ibid. 42-43).

Moreover, Christ did not descend to the earth as a spirit who despises the material world but instead He took on human flesh and in so doing elevated our understanding of our material bodies because it is through the soul and body that Christ united Himself to all of humankind in order that he might redeem us.

For this reason, we should not overlook the value of a healthy body for ourselves and for those around us, while being mindful that “health is always a matter of partial and temporary equilibrium,” as Larchet notes.[1] At the same time, we should not desire to cripple our own bodies through severe ascetic disciplines, which will cause us to need the care of those around us because we crushed our bodies in an undiscerning manner.

The Cause of Her Sickness

Generally, throughout the Gospels, there is no explanation about why someone has a particular ailment. There are many instances where people were brought to Jesus who had diverse diseases, palsy, or were possessed by demons and were healed for no other reason but because they were brought before Him.[2] Others were healed either due to their faith such as the woman with an issue of blood (Mark 5.25-34; Luke 8.43-48), or the Ten Lepers (Luke 17.12-19); or the faith of others such as the centurion’s daughter (Matt. 8.5-13; Mark 5.23; Luke 7.2-9), and Jarius’ daughter (Mark 5.22-24). In these examples, there is no indication as to why they suffered what they have.

We can compare the healing of our woman in the Gospel reading today with the parable of the Good Samaritan. In this story, we learn of a man who fell among thieves. All passersby avoided him - a priest passed him by on the other side, a Levite passed by on the other side as well, and only later is he attended to by a Samaritan (Luke 10.30-37). Again, there is no indication as to why the man suffered such misfortune?

Another example is that of the man who was born blind, and Christ’s disciples outrightly posed the question: “Who sinned that this man was born blind, he or his parents?”(John 9.1-7), to which Christ replied that neither had sinned because the reason for the man’s infirmity was so that the works of God should be made manifest in Him (vs. 4).

St. Nicholas Cabasilas notes that there are certain bodily ills that come to us because of the wickedness of our souls, but Larchet is quick to note that these cases are rare. Further, he writes:

We should not read into them some naïve notion of punishment, whether out of anger or as a mechanical reflex, inflicted by divine wrath. Rather, they represent providential ways to salvation, in that for the person concerned they serve most adequately to lead them to recognize, through the sudden misery of their body, both the illness of their soul and their estrangement from God.[3]

St. Gregory of Nazianzus (the Theologian) writes to a friend who is sick and encourages him to understand its purpose and not see his sickness as the wrath of God:

I don’t wish and I don’t consider it good that you, well instructed in divine things as you are, should suffer the same feelings as more worldly people, that you should allow your body to give in, that you should agonize over your suffering as if it were incurable and irredeemable. Rather, I should want you to be philosophical about your suffering and show yourself superior to the cause of your affliction, beholding in the illness a superior way towards what is ultimately good for you.[4] (“philosophical” meaning to consider what the sufferings reveal about one’s condition)

Such are the variations for health in all men, the cause of which is only discerned by the spiritually wise.

The Compassion of Christ

What if the woman in today’s Gospel reading was responsible for her ailments, should we then be less sympathetic, less charitable, less compassionate towards her? Does she “get what she deserves” then? If it is her own fault, does that free us from the responsibility of showing compassion? St. Isaac says, “You, however, have not been appointed to decree vengeance upon men’s deeds and works, but rather to ask for mercy for the world, to keep vigil for the salvation for all, and to partake in every man’s suffering, both the just and the sinners.”[5] (Is there anything else for us to do for others?)

Even if we think there might be some connection, and of course there may be when it comes to bodily illnesses that are a result of moral depravity because passions do leave their imprint on the body, yet it is not up to most of us to discern these things. Even if we do know the cause, we are not to judge but to imitate the Lord who, although He knew those who killed his friends, the prophets, He loved them and prayed for them saying, “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou that killest the prophets, and stonest them which are sent unto thee, how often would I have gathered thy children together, even as a hen gathereth her chicks under her wings…!” (Matt. 23.37)

On a similar occasion to our Gospel reading, before the Lord went into the temple on the Sabbath and healed a man with a withered hand, he says, “But if ye had known what this meaneth, I will have mercy, and not sacrifice, ye would not have condemned the guiltless” (vs. 7). When He saw the widow of Nain whose dead son was being carried to burial, the Lord saw her, the Apostle Luke records, “and He had compassion on her” then raised her son to life (7.13). Before the miracle of the feeding of the five thousand, the Apostle Matthew records that He “saw a great multitude, and was moved with compassion toward them, and he healed their sick” (Matt. 14.14).

Conclusion

Perhaps, it is easy not to judge our brothers and sisters if we do not see their faults. If we do see their faults and we judge them, we injure our own soul let alone potentially damage and crush that of our brother. However, when we see their faults and, overlooking them, love them nonetheless, this is the way of God.

Is this what the Lord meant with the woman caught in adultery, that if we knew our own sins we would not accuse others, or perhaps not see them in others and be only aware of our own?

As the Apostle Paul knew the crimes against God committed by his own people yet, with “great heaviness and continual sorrow,” he desired that he would be accursed from Christ on their account, if only they would be saved (Rom. 9.3).

May we, and I first, look with compassion on all of humanity and look not towards judging, but pray for their salvation and find means to comfort others in soul and body.

THROUGH THE PRAYERS OF OUR HOLY FATHERS, LORD JESUS CHRIST OUR GOD, HAVE MERCY ON US. AMEN.

[1] Larchet, Jean-Claude. The Theolgy of Illness. (Crestwood, St.Vladimir Seminary Press, 2002), 53.

[2] cf. Matt. 4.24; 8.16-17; 9.14-15; 12.7-15, 22; 14.14; 15.30; 19.2; 21.14; Mark 1.34; 3.10; Luke 4.40; 5.15; 6.17-19; 9.11

[3] The Theolgy of Illness, 51.

[4] Letters XXXI. 2-3 in The Theolgy of Illness, 58.

[5] Homily Sixty-four, 457.

Leave a comment