I Have Enough - Homily for the Feast of the Meeting of the Lord (2023)

Ich habe genug. I have enough. So sings the Elder Symeon in the well-known cantata composed by Bach for this feast day. I have enough. It’s a peculiar sentiment, one that we’re not well acquainted with as 21st century Americans. “I have enough,” isn’t good for the economy. “I have enough,” hurts quarterly profits. If we all had enough, there would be no Amazon Prime. No, our society marches to a different tune—“I can’t get enough.” We’ve perfected the science of manufactured demand. Each demand’s satisfaction is short-lived, and so we become conditioned to live from purchase to purchase, from meal to meal, from show to show, video to video, post to post. Each pleasure is fleeting as the last, and we grow restless looking to the next thing. Passion and vice are inherently derivative, repetitive, barren, bereft of the true spark of life and creativity. They exist parasitically on God’s good creation. When we’re beholden to them, they continually submerge us in a roiling sea of desires and cares. They keep us from ever being content and grateful, from ever saying, “I have enough.” We grow weary from our perpetual desire for passing things, and end up frustrated and bored. This isn’t just the plight of our consumerist culture, though. It’s a story as old as humanity itself. As King Solomon says, Vanity of vanities; all is vanity … The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun (Eccl. 1:2, 9).

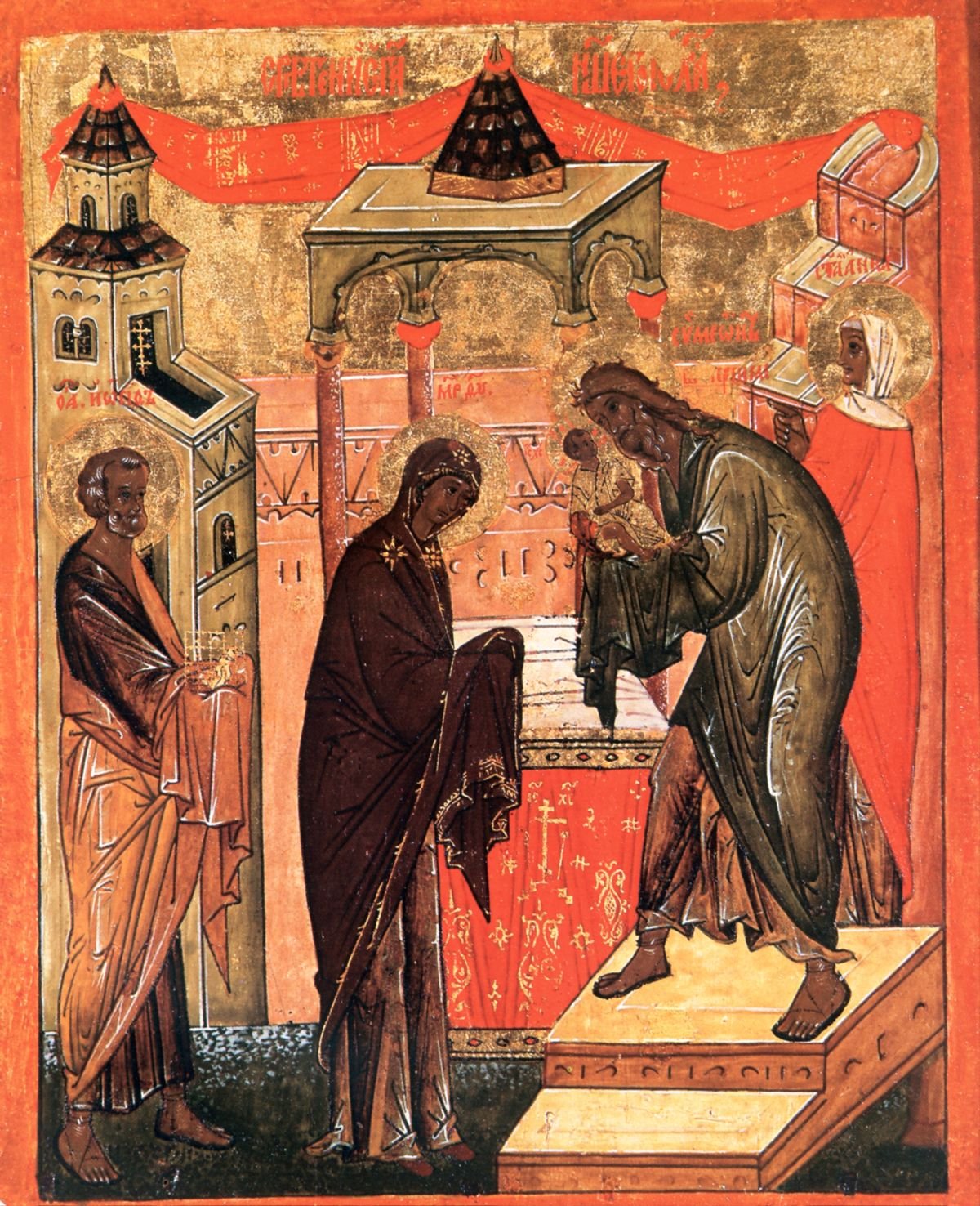

Imagine the profound world-weariness of the aged Symeon, who as some of the Fathers teach, had been miraculously preserved in this life for over 300 years. Imagine then his profound joy at taking into his feeble arms the one thing new under the sun, the divine Infant, the Sun of righteousness, our Lord Jesus Christ. That should give you a sense of the joy we too ought to feel on this day.

This feast is one of the most unique of the Church year. For one, it is both a feast of the Lord and of the Mother of God. Many things meet together today—light and shadow, law and grace, birth and death, old and new, Jews and Gentiles, God and man. This day also stands as a meeting point for the two great cycles of the liturgical year—the one that’s ending, which commemorates the Savior’s birth, and the one that’s just beginning, which commemorates His death and resurrection. The shadow of Great Lent and Holy Friday always looms over this feast, sobering its joy and suffusing it with a certain somberness. This isn’t just a coincidence of our liturgical calendar, though. It belongs to the very nature of the events recounted in the Gospel.

In the Western Church, this feast is typically called the Purification of the Virgin. Our faith tells us that the Virgin incurred no defilement from her sinless, seedless birth. But just like the sinless Lord’s baptism in the Jordan, the all-pure Virgin comes to be purified in order to fulfill all righteousness. She had no need of bodily purification; yet as one born under the curse of the first Adam, she still required purification and redemption from the stain of ancestral sin. Though she was personally without sin, she still had to be perfected through sufferings.

This is what Symeon promises her when he says, Yea, a sword shall pierce through thy own soul also (Lk. 2:35). In the Spirit, Symeon foresaw that the forty-day-old Infant whom he held in his arms would someday be tortured and hung on a Cross. His penetrating gaze passed over all of the promise and the joys of newborn life, and saw through to the tragic, sacrificial death that awaited the Savior. In that moment, he warned the Mother of God of that dreadful hour, and of the unspeakable suffering she would have to endure at the foot of her Son’s Cross.

As Symeon prepares to depart this life, he urges the new mother not to rest complacent in the joys of life that lie ahead of her, but keeps her mindful of life’s inevitable end. Now that we finish celebrating the liturgical cycle of the Lord’s birth, the Church, like Symeon, directs our gaze to the Cross and death of the Lord. She tells us, in effect, that if we want to find rest in God and greet death joyfully like Symeon, then we must embrace the Cross of the Lord. If we want to say like Symeon, “I have enough,” a sword must also pierce our hearts.

What is this sword? It’s nothing other than love for the crucified Christ, which draws us to the foot of His Cross, to stand in sorrow and solidarity with the Mother of God. We can never know the depth of her suffering because we do not share the depth of her love. Still, we must endure our own measure of inner suffering in order to abide steadfastly in the love of God.

The sword of God’s love wounds our hardened heart with compunction, bringing us tears for our sinful condition and tearing us away from all of the habitual vanities of this life—passions, possessions, even family and friends, all of the things we use to cover up our spiritual nakedness and find satisfaction in life apart from God. The stripping away of our heart’s sinful attachments is a painful, agonizing process. We think we love God well enough, but we’d rather not suffer too much for Him. Though we grow weary of our vices and pleasures, yet there’s a comfort and familiarity to them that we often retreat to when we’re confronted with suffering. As Christ says, No man having drunk old wine straightway desireth new: for he saith, The old is better (Lk. 5:39). Yes, to our taste the old wine of earthly pleasure is better than the potent draught of God’s love. That’s because, in our carnal state, love for God requires pain of heart. Until we learn to strip away our attachment and desires, we will continue to prefer the old wine, no matter how sick it makes us.

The approaching Fast is the special season the Church gives us to help us in the struggle to detach ourselves from our spiritual entanglements with the world. We all understand the benefit that comes from struggling together during Lent as a whole community and even as a whole Church. But ultimately, no one can take the burden of struggle away from us. We have to walk the rough way to Calvary each one of us ourselves. If we feel a certain amount of dread and trepidation at the crucifixion we must undergo, we shouldn’t be disheartened. Even Christ endured His agony in the garden before He underwent His Passion.

But like Christ, let us emerge from the struggle victorious. As monks, we shouldn’t stagger at the pain and difficulty of our vocation. Pain of heart is the sign of a genuine monk, a monachos, a solitary. We have to embrace the fundamental loneliness of our spiritual task to rid ourselves of every earthly attachment, in order to abide alone with the one God. Even those who have not renounced the consolations of a spouse and a family ought to be as though they had none, as St. Paul says (1 Cor. 7:29). For in the final analysis, we are all alone. We must all come face-to-face with Christ, “where no one will be able to help us, but our deeds will condemn us,” (Canon of Repentance, Ode III). If we refuse earthly consolations and seek the face of Christ with pain of heart, then we will eventually delight in the new wine of divine love. But if we waver, overwhelmed by despair at our suffering, and seek refuge in the fleeting pleasures of life—even those that are good and lawful—then sooner or later, our meeting with the Lord will come. Only we won’t greet it joyfully as did Symeon.

So though we know that the sword of Great Lent stands ready to pierce our souls with fasting and abstinence, let us go towards it eagerly, knowing that its bitterness will bring us great benefit. Let us not cling to comforts and indulgences, but as St. Paul says, having food and raiment, let us be content therewith (1 Tim. 6:8). The fewer needs we have, the more easily we will be able to say, “I have enough.” And so, unburdened of carnal desires and earthly cares, we will be able, joyfully, to meet the risen Lord on Pascha night. Amen.

Leave a comment